Is it time to do away with "male gaze" criticism?

And a surprising fact about girl/girl content.

Around this time last month, I went to a convention for the first time since the pandemic began. New York Comic Con was, while subdued (and highly focused on anime), still filled with just as much art as ever. And that included plenty of illustrations depicting skinny, toned, muscular white superheroines with their hips and chest out, posing suggestively for the viewer.

It’s kind of a stereotype at this point: The average white guy artist at a comic convention either sells grimdark stuff, artwork inspired by Golden Age comics, or some of DC and Marvel’s most attractive women in skintight suits with their heaving breasts bared breastily. And yet, as a self-professed pervert, I should refrain from casting a stone from a glass house. After all, haven’t I enjoyed pin-up artwork by thirsty leatherdykes showing hourglass femme dommes in similar getup?

This got me thinking a lot more about objectification in media, and what the “male gaze” really is. For sure, it remains an important tool for feminist media critics. But I suggest we levy the phrase “male gaze” far more cautiously in our work, lest we speak over other queer women.

Defining the “male gaze”

Laura Mulvey first developed the theory behind the male gaze in her 1975 work “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” The essay hasn't quite aged well (its opening argues women in cinema symbolize “the castration threat by her real absence of a penis”), but there’s still quite a bit of relevant commentary to be had through Mulvey’s overview.

Most importantly, she lays out the ways in which patriarchal power is maintained through film. Calling on Freudian psychoanalysis, she points out how male filmmakers treat their movies’ women as erotic objects for male characters’ and viewers’ pleasure alike. We become voyeuristic vehicles that reaffirm patriarchal norms.

"In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female," she wrote.

"In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Women displayed as sexual object is the leit-motiff of erotic spectacle: from pin-ups to strip-tease [...] she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire."

To update Mulvey’s argument to 2021, let’s define the male gaze theory as:

“A theory of feminist criticism that argues women commonly exist in media as vehicles for sexual desire and pleasure, in that their bodies are depicted, designed, and displayed to,

Be consumed by the straight, cisgender, heterosexual-assumed male viewer’s pleasure

For the benefit of straight, male, cisgender characters, and

To reinforce larger misogynistic sociocultural beliefs about women’s bodies”

Does the “male gaze” exist? Nearly 50 years after Mulvey came up with the idea, it’s still strikingly true that straight men tend to depict women first and foremost in ways that pleasure themselves and other straight men. Women must be beautiful, in the sense that they are cis, thin, sexually available at a moment’s notice, and they must successfully perform their patriarchal expectations or face an untimely demise. This voyeuristic urge is still prevalent in media, and because entertainment remains dominated by cishet men, the “male gaze” continues.

The limits to “male gaze” critique

All that may be true, but I want to push back against the idea that art can be defined in a binary: “male gazey” or “not male gazey.” This seems far too simplistic to me, because art is not static. It’s ever-changing in nature and primarily defined by the perspective of those perceiving it.

First, let’s break down how the male gaze actually operates. For a work of art to be engaging in the male gaze, it must have both

intention by the creator, and

an appeal to the viewer in a patriarchal way

This poses a problem for analyzing whether a work of art is engaging in the male gaze, because the male gaze only exists if it appeals to the male viewer’s existent gaze. Patriarchy and heteronormativity are living, breathing cultural forces that change with the times, and the manner with which they express themselves age. This means that a work of art created with patriarchal values may be read as patriarchal shortly after its creation, but as time goes on, that same piece of art may be read as campy, over-the-top, and queer later on in its lifetime.

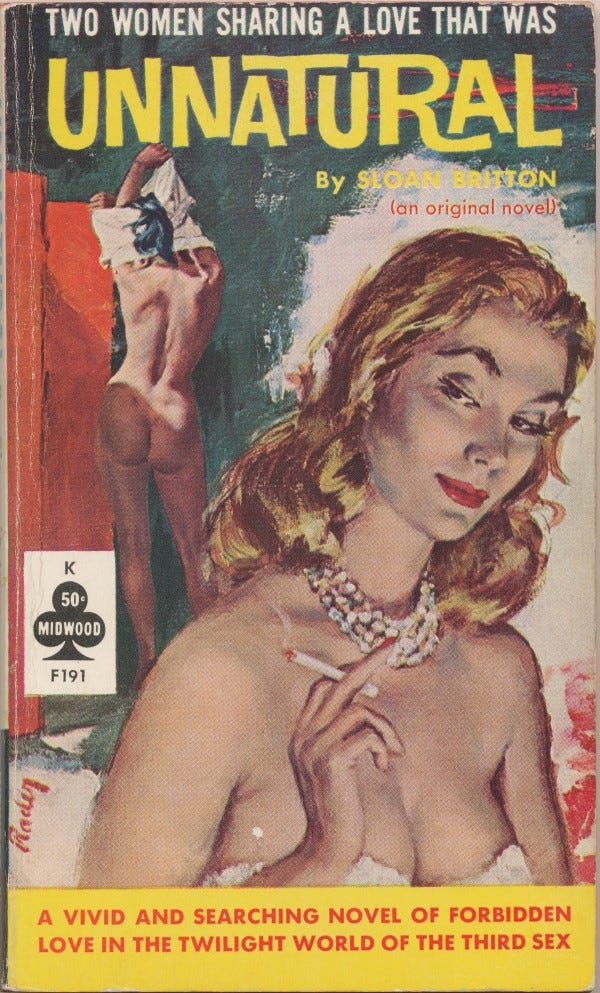

A classic example of this is the immense popularity of “lesbian pulp fiction” covers on Twitter and Instagram. These images, with titles such as Passion Pusher and Women Without Morals, are often celebrated by today’s lesbians for their dramatic depictions of sultry femmes seducing and bedding young women.

While lesbian pulp fiction was written predominantly for a straight male audience during its time, lesbian pulp fiction today is too outdated and too gouache for the straight gaze; now, it has a queer following because of its exaggerated performance of femininity, not in spite of it. The pulp femme top embodies the femme gender presentation’s core, a "defiant and knowing femininity, performed for oneself and for other women, rather than in service of the heteronormative status quo," as Kesiena Boom writes for Slate. She is not simply a woman, but a dominant, a seductress, a mommy. Even in its heyday, pulps’ campy, over-the-top attributes gave cover to queer women: Many found representation and belonging in these novels, especially through women writing for lesbian women, who slipped under the radar due to heterosexual assumptions about who gazed at whom.

The pulp paradox continues today through girl/girl porn and its viewership. According to Pornhub's 2019 statistics, women viewers’ most popular category was by far lesbian porn, with a 147 percent proportional difference in popularity compared to their male counterparts. Traditional arguments suggest that most g/g lesbian porn is “is made for cis men, regardless of who’s involved in the scene.” There’s truth to that, and yet, women specifically seek out lesbian porn at a higher rate than men.

Theories abound why this happens. Most argue the source is straight women disenchanted with straight porn; one sex therapist told HelloGiggles that lesbian porn focuses more on women's pleasure than its straight counterpart, while another sex expert claims straight women "may like it because it might be taboo for them and it piques their curiosity." But according to a 10,500-person survey from Dazed Digital, the only demographic that outpaces straight women for watching girl-on-girl porn is, you guessed it, gay and bisexual women. And an additional study by Autostraddle reveals that, while queer women are more likely to watch porn by queer creators, 30 percent still watched lesbian porn videos by and for straight people. Despite claims that mainstream lesbian porn is cringey, problematic, unrealistic, and aggressively male gazey, sapphics are still tuning in.

This highlights a problem with the “male gaze” theory. It does not compensate for the fact that media may be interpreted and engaged with from a kaleidoscope of angles based on age, class, gender, sexuality, learning history, and sociocultural era. The death of the author—the acknowledgment that text and intention are not one and the same—applies to all forms of artwork, including pornographic and erotic material. The male gaze is a matter of both communication and reception, and boisterous, authoritative criticism may obfuscate the multifaceted ways queers relate to art.

Just as media can be read queerly, work seemingly created by and for cis men can also host wedges, nooks, and crannies for queer women to find a home. The author’s intent may be irrelevant to a queer viewer who will take a piece of artwork and refashion it until it brings about pleasure and joy unrecognizable to its creator. This means the non-male gaze is equally important when analyzing art, as the seemingly “male gazey” piece may be deemed campy, satirical, tongue-in-cheek, or even relatable by a queer viewer from a different time, a different place, and from a different sociocultural background than others.

That’s not to write off the “male gaze theory” as a tool. When I walked around New York Comic Con, it was obvious that the expo hall’s straight cis men drew its highly desirable, highly exaggerated female figures from a place of voyeuristic pleasure rooted in patriarchal desires for how women should look and behave. But not all pin-up art and scantily clad women are created equally. And a queer woman may see things in a comic or illustration that its straight cis male creator could never foresee, things that reveal how art is far more complicated than just one person’s intent.

Special thanks to Louise Ashley Yeo Payne and Jacqie for their generous Sex-Haver contributions.